I won't declare this blog dead -- I still have notions of adding to it when I find the time -- but, for now, I'm turning some of my energy to a new blog, You Could Look It Up, a kind of companion to the book I'm writing.

24 August 2011

30 December 2010

Year in Review

A none-too-fond glance back at calendar year twenty-oh-ten:

- Courses taught: 4

- Students taught: 206

- Number of undergraduates among them: 191

- Number of those undergraduates older than my cat: 3

- Amount of respect I can have for students born after 1990: 0

- Plagiarists busted: 3

- New books published in hardback: 2

- Old books published in paperback: 2

- Old books published in audiobook format: 1

- Highest Amazon.com ranking for any of those books: 110

- Lowest Amazon.com ranking for any of those books: 4,959,391

- Articles published: 6

- Book reviews published: 12

- Journal volumes published: 1

- Articles and reviews edited, copy edited, and proofread: 71

- Typescripts of new books delivered to publishers: 1

- Single-spaced pages of notes accumulated for the next trade project: 574

- New book contracts received: 2

- Nights in which I got an adequate amount of sleep: 0

- Conferences attended: 6

- Presentations delivered: 3

- Estimated expense of travel, lodging, and registration at these conferences: $1,600

- Conference trips paid for, in whole or in part, by Rutgers: 0

- Amount spent on two taxi rides in a single week in April: $395

- Expert opinions delivered in legal cases: 2

- Radio interviews to flog The Lexicographer's Dilemma: 5

- Letters of recommendation written: 22

- Letters written for promotion and tenure cases: 4

- Anonymous referee's reports on scholarly books: 7

- Anonymous referee's reports on scholarly articles: 11

- Hours wasted in pointless committee service: 1.3 x 1024

- Visits to hospital emergency rooms: 3

- Encounters with boneheaded doctors who made my condition far worse, in one case requiring an additional trip to the emergency room: 2

- Tracks newly added to my iPod: 10,012

- Number of days it would take to hear those songs, listening around the clock: 28.5

- Estimated ounces of tea drunk: 4,380

- Estimated milligrams of pure caffeine in that tea: 46,538

- Estimated ounces of wine drunk: 2,950

- Estimated ounces of pure alcohol in that wine: 369

- Number of Four Lokos it would take to get the same buzz, for caffeine and alcohol respectively: 298, 128

- Inadequately acknowledged ripoffs of Harper's Index: 1

Posted by

Jack Lynch

at

9:47 AM

7

comments

![]()

16 November 2010

Near-Death Experience

First post in a long, long time. Shame on me. Life has been uncommonly busy the last few months.

It didn't help that I lost most of a day yesterday to a health-related much-ado-about-&c.

Nope: they interpreted "congestion" as "difficulty breathing," then somehow added "chest pains" to the list (where did that come from?). They said they couldn't in good conscience let me leave without zipping me to the emergency room. My protestations were in vain: clearly I was in denial. I got to enjoy an ambulance ride to the hospital, all of four blocks away ("Are you able to stand on your own, sir?"), where I experienced four hours of that unique combination of stifling boredom, extreme discomfort, and nagging anxiety you find only in a hospital. I got EKGs, X-rays, blood work, all kinds of mean, nasty, ugly things, and they was inspecting, injecting every single part of me, and they was leaving no part untouched.

Finally they released me, in more or less the condition I was when I came in.

Well, less. I nearly had to go back to another ER a few hours later.

During the day I listed for the nurse all the drugs I take. They then treated me with Albuterol to ease the congestion in the lungs. That'd be swell, except that, as I discovered when I read my discharge instructions on the train ride home, Albuterol interacts very badly with one of my meds: the warning sheet advises "extreme caution" if you take them within two weeks of one another. I made a few calls, and my pharmacist and my internist warned me that I might experience tachycardia and hypotension. Boy, they wasn't kidding: all night my heart was pounding at 120+ bpm and my blood pressure was 103/57.

I've come to accept that I'm probably not marked for great things in this world. I do hope, though, to have something slightly more impressive on my tombstone than "He died at forty-three of post-nasal drip."

Posted by

Jack Lynch

at

4:55 PM

3

comments

![]()

01 June 2010

You Could Look It Up: Suggestions Solicited

My next trade book is under contract; it's provisionally titled You Could Look It Up: The Reference Shelf from Babylon to Wikipedia. It'll be a whirlwind tour of reference books, broadly understood — dictionaries (general and specialized), encyclopedias, atlases, concordances, medical and legal compendia, sports statistics, even telephone directories and tables of logarithms. I'll also include plenty of digressions, in the form of sidebars or interchapters, on things like the history of alphabetical order, people who've read reference books from cover to cover, ghost words and mountweazels, and so on.

Something that has come to me since I got the contract: I'm keen to get input from prominent bookish people on their experience with reference works. I'd love to know what, say, Umberto Eco or Richard Posner have to say about reference books. I'm therefore putting together a very brief questionnaire — maybe five or six questions — and sending them to a few dozen such people. I'll go through channels when possible, and resort to cold-calling when necessary. The answers will then appear throughout the book in sidebars, little boxes, to accompany the main text.

There are two things on which I'll be grateful for advice from readers. The first is whom to approach. I've got a few dozen names in mind already, including people like Sven Birkerts, Alberto Manguel, Paul Krugman, Oliver Sacks, Mary Beard, David Lodge, Pierre Bayard, Simon Schama, Doris Lessing, Atul Gawande, Amartya Sen, Seamus Heaney, A. S. Byatt, Steven Pinker, Alan Lightman, and Isabel Allende. I know how to get to some of them, and will be looking for approaches to others.

I welcome suggestions for more names to add to the list — who will have interesting things to say about dictionaries, encyclopedias, and so on? I'd like the list to be as international as possible (European publishers have expressed interest in the book); I also want diversity of interests: poets, novelists, historians, theologians, scientists, legal scholars, and so on.

The second question is what exactly to ask them. Requests for free-form essays is unlikely to get any replies; instead I need a small number of focused questions. Here's what I've got now:

- Is there a reference work you couldn't do your job without?

- Do you have a favorite obscure reference work that deserves to be better known?

- Do you have a favorite entry in a reference work?

- What was the first reference work that caught your attention when you were young and why?

- How do you organize your own reference collection in your house, apartment, or office?

Posted by

Jack Lynch

at

10:11 AM

9

comments

![]()

09 April 2010

This Is Why We Have Adverbs

A story in the New York Times comes with this wonderful lede:

Doctors at Bagram Air Base were stunned to find unexploded ordnance lodged in an Afghan soldier’s head. They removed it very carefully.

Posted by

Jack Lynch

at

9:21 PM

2

comments

![]()

15 November 2009

New Language Blog

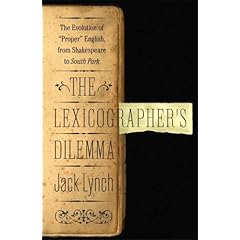

Since I started this blog at the end of '07 I've used it only intermittently, mostly for passing snarkery. It means I sometimes go weeks, even months, between posts. With my new book out, though, my publisher has been keen to find ways to promote it, and a bit of correspondence between my publicist and the folks at Psychology Today led to an offer to write a blog there. I've agreed, with a brand new hot-off-the-presses blog called Proper Words in Proper Places. (It was my original title for The Lexicographer's Dilemma — I'll get to use that quotation from Swift somewhere, dammit.)

With my new book out, though, my publisher has been keen to find ways to promote it, and a bit of correspondence between my publicist and the folks at Psychology Today led to an offer to write a blog there. I've agreed, with a brand new hot-off-the-presses blog called Proper Words in Proper Places. (It was my original title for The Lexicographer's Dilemma — I'll get to use that quotation from Swift somewhere, dammit.)

I've just begun it with an introductory post, spelling out the topics I plan to discuss. And whereas this one will continue to be used for occasional musings, I hope to weigh in there at least weekly. I welcome queries and suggestions.

Posted by

Jack Lynch

at

3:50 PM

0

comments

![]()

02 September 2009

On Google Books

Geoffrey Nunberg has a smart essay in The Chronicle of Higher Education on some of the limitations of Google Book Search. Plenty of people have groused about the problems they've encountered, but Nunberg gets to the heart of the problems by focusing on Google's shoddy treatment of "metadata":

I'm actually more optimistic than some of my colleagues who have criticized the settlement. Not that I'm counting on selfless public-spiritedness to motivate Google to invest the time and resources in getting this right. But I have the sense that a lot of the initial problems are due to Google's slightly clueless fumbling as it tried master a domain that turned out to be a lot more complex than the company first realized. It's clear that Google designed the system without giving much thought to the need for reliable metadata. In fact, Google's great achievement as a Web search engine was to demonstrate how easy it could be to locate useful information without attending to metadata or resorting to Yahoo-like schemes of classification. But books aren't simply vehicles for communicating information, and managing a vast library collection requires different skills, approaches, and data than those that enabled Google to dominate Web searching.

There's much to agree with there. I adore Google Books, and would have a hard time getting by without it, but they really have to devote more energy to these concerns. Here's hoping the high-profile finger-wagging will get Google to pay more attention to cataloguing.

Posted by

Jack Lynch

at

2:45 PM

1 comments

![]()

01 September 2009

Reading over People's Shoulders

Once upon a time, the only way to get feedback on a book you wrote was to wait for published reviews. That could take a long time. Much of my writing has been in the academic world, and there it's not unusual for your first review to appear a full year after publication. In the world of trade publishing, where publishers usually send out advance copies for review, you start seeing the first few reviews a few weeks before the book is on the shelf. Still, that's typically a year after the book has been finished. I'm impatient.

Since the mid-1990s, it's been possible to track the popularity of books in Amazon.com's sales rank. Mind you, one of my books doesn't even make the top 7.5 million sellers in America, and even my current best seller is around number 250,000, so perhaps "popularity" isn't the best word. I don't think Dan Brown and J. K. Rowling have to worry about my overtaking them anytime soon.

Even in the Amazon age, though, the feedback is very limited and sporadic. But now, thanks to Google Alerts, I can now see every stray comment about my book the moment it appears on the Web — every blog post, every passing comment in a newsgroup, every reader's review on a book sales site.

This is much on my mind as The Lexicographer's Dilemma is about to be published by Walker & Co. in early November.  (It's available for pre-order from Amazon.com, though it's far better to support independent booksellers whenever you can; the ABA deserves mad props.) The first professional review hasn't appeared anywhere, and yet I've been reading over the virtual shoulders of my readers for more than a month and learning what they think of it. I've found it enlightening to read comments on blogs I'd never heard of, like this one from You'll Eat It and Like It, or this one from KingTycoon on LiveJournal.

(It's available for pre-order from Amazon.com, though it's far better to support independent booksellers whenever you can; the ABA deserves mad props.) The first professional review hasn't appeared anywhere, and yet I've been reading over the virtual shoulders of my readers for more than a month and learning what they think of it. I've found it enlightening to read comments on blogs I'd never heard of, like this one from You'll Eat It and Like It, or this one from KingTycoon on LiveJournal.

One new development that deserves attention is LibraryThing, a service that makes advance review copies available to layfolk. Of course I got an ego-boost from seeing that LexDilem was among the "really popular books" among LibraryThing participants (more than two thousand requests for thirty-five free copies), though that just means more negative reviews if the book is a dud. I suppose some authors might be upset that these readers are getting free copies instead of paying for them, but I'd just as soon see dedicated readers get their hands on the book as soon as possible if they're willing to spread the Gospel of Lynch. As of 1 September, there are six reviews on LibraryThing, and so far they're all pretty good (an average of 4.2 stars out of 5 — I'll take that).

Reading reviews and other comments by amateur reviewers is a strange experience. On the one hand, it's a treat to get a sense what real readers think about your writing; on the other, at least a few of those readers can be downright cranky. (One of my books once got a one-star review on Amazon.com because Amazon shipped it too late to be useful to the reader. I notice Amazon axed the review, though whether it was to protect my reputation or theirs is unclear.)

One reviewer (in a generous reivew) notes that "clearly [Lynch] sides with the descriptivists in most every way," which is kinda funny for someone who wrote a thoroughly prescriptive guide to grammar, style, and usage. I've generally resisted the urge to add my own comments to the blogs and discussion forums, thinking that's just a high-tech version of what Paul Fussell memorably described as the "A.B.M." — the Author's Big Mistake of responding to book reviews. But it's not easy to stay quiet, especially in a forum that begs for interaction. (I've also resisted the urge to post anonymous positive reviews of my own books on Amazon.com, the sort of thing James Boswell was doing 250 years ago.)

As I note on the page of shameless self-promotion, where I collect the more prominent professional reviews my books have received, "I'm happy that (so far) I've received no unambiguously negative reviews (though a few have had their reservations)." I suspect that LexDilem is the book that'll change that. People can be surprisingly passionate, or stubborn, about their likes and dislikes in the language, and the odds are good that some reader will be infuriated. Oh, well. It was a good run while it lasted.

Posted by

Jack Lynch

at

10:14 PM

1 comments

![]()

07 July 2009

Cricket Made Simple

I see the first Ashes test match is starting. After much research, I've finally made sense of cricket.

It turns out it's actually very simple. Someone throws a ball at someone else, who whacks it with a wide stick. After that, everyone runs around the field — yes, field, not "pitch," because pitching is what you do with the ball, not "bowling," because we all know bowling involves rented shoes — everyone runs around the field helter-skelter, randomly going in any direction, while the announcer makes up as many funny-sounding phrases as he can think of, like "silly midwicket," "googly," "diamond duck," and "maiden over." Then they announce that the score is "[some three-digit number] for [some one-digit number]," and everyone nods and pretends to understand. They do this for up to three days, taking occasional breaks for tea, and then go home.

Lewis Carroll understood this well in his description of the caucus race:

First [the Dodo] marked out a race-course, in a sort of circle, (the exact shape doesn't matter, it said,) and then all the party were placed along the course, here and there. There was no One, two, three, and away, but they began running when they liked, and left off when they liked, so that it was not easy to know when the race was over.

Posted by

Jack Lynch

at

10:19 PM

9

comments

![]()

14 June 2009

Stunning

I was astounded to hear the results in the Stanley Cup finals, in which the Penguins beat the Red Wings.

The surprise: who knew we still had a hockey league?

Posted by

Jack Lynch

at

8:39 AM

2

comments

![]()